Most

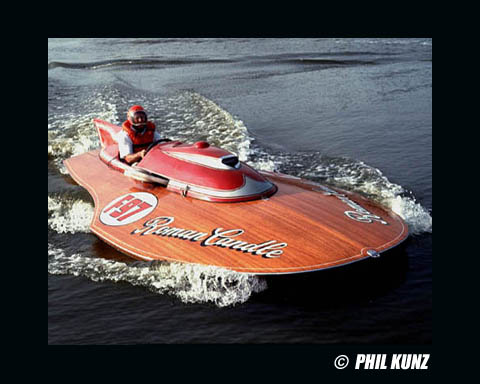

of the hull designs on these pages are ones that were successful during

the time period of from 1950 to 1975. Opinions vary about their successfulness,

but the fact that people were trying anything that would  give their particular

hull design a competitive advantage is historically worth mentioning. Books

could be written oncertain designers such as Henry Lauterbach, who has

over 200 documented hulls he designed and built over a 40 year period.

Some builder/designers handcrafted less than 2 or 3 hulls during their

lifetime.

Varying backgrounds of each of these builders probably played a role in

the way they were built, but one thing they all must of had in common was

a love of woodworking. give their particular

hull design a competitive advantage is historically worth mentioning. Books

could be written oncertain designers such as Henry Lauterbach, who has

over 200 documented hulls he designed and built over a 40 year period.

Some builder/designers handcrafted less than 2 or 3 hulls during their

lifetime.

Varying backgrounds of each of these builders probably played a role in

the way they were built, but one thing they all must of had in common was

a love of woodworking.

Each builder must have believed that their hull

would have an uniqueness of special characteristics that would make their

hull faster and different from the others.There are abundant stories you

will hear about the characteristics of a particular hull. Each builder must have believed that their hull

would have an uniqueness of special characteristics that would make their

hull faster and different from the others.There are abundant stories you

will hear about the characteristics of a particular hull.

Different theories on such items as the placement of the sponsons on the

hull, angles on the chines, the beam width at the front, middle, and aft

section and how those dimensions flow into the right combination for speed

in the straightaways and the turns.

Each hull would be tweaked trying to

find the ultimate agility, responsiveness, and total overall handling needed

by the driver to be the first across the line. Some hull ideas worked,

some did not.

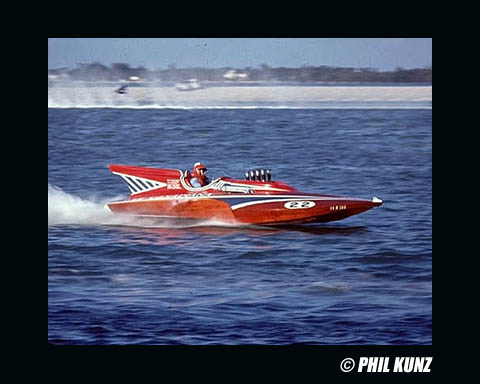

Prior to the late 1960's, the round nose 3-point hydroplane design was

dominant. This design was basically patterned off the Slo-mo-shun IV that

Ted Jones designed and Anchor Jensen built. This hydroplane shattered the

world water speed record, then the egos of its competition when in debuted

in the unlimited ranks in 1952. From then on, all the style designs of

hydroplanes basically adopted this design.  Even the stepped, displacement

V-hulls (the original "hydroplane") which were an improvement over the

conventional V-hulls, with having their "notched" out steps in the bottom

of the hull, were no match for the 3-point hydroplane. Even the stepped, displacement

V-hulls (the original "hydroplane") which were an improvement over the

conventional V-hulls, with having their "notched" out steps in the bottom

of the hull, were no match for the 3-point hydroplane.

This

style of hull would literally fly over the water and therefore eliminate

the water resistance problem. With their propeller about 50% out of the

water, huge amounts of water would be displaced into the air behind the

racing craft creating the famous roostertail that was associated with these

hydroplanes.  With most round nose hydroplanes, the motor was in the front

and the driver was seated behind the motor in the rear of the hull with

the drive shaft running underneath the driver. With most round nose hydroplanes, the motor was in the front

and the driver was seated behind the motor in the rear of the hull with

the drive shaft running underneath the driver.

No seat belts were

worn by the drivers, with

the thinking that in case of a blowover, if would be wiser to be thrown

from the hull, than to be strapped into a wood craft that could literally

disintegrate upon contact with the water.

These

builders all contributed to the different styles and looks you see in vintage

hydroplanes. These gentlemen would make hydroplane modifications, adding,

subtracting, moving and refining the many angles that grace these racing

machines. Another item worth noting that these men were also very good

boat racers. This on-hands experience I'm sure attributed to the many major

and minor distinctions you see between the different names in the hydroplane

raceboats. These

builders all contributed to the different styles and looks you see in vintage

hydroplanes. These gentlemen would make hydroplane modifications, adding,

subtracting, moving and refining the many angles that grace these racing

machines. Another item worth noting that these men were also very good

boat racers. This on-hands experience I'm sure attributed to the many major

and minor distinctions you see between the different names in the hydroplane

raceboats.

Using

experience from racing and testing, they would try to improve and build

into their designs any hull requirement they thought would be needed to

win. Changes and modifications were construction techniques, different

framing types, fastening systems, plywood thickness selections, driveshaft

angle, and motor placement. I'm sure many of the driver/owners were also

pitching in their 2 cents worth with reports on water conditions on the

different courses in the regions. These handling characteristics of the

different hydroplane designs and the new changes would spread between the

racers. All these new changes eventually evolved into hydroplane hull styles

we see today.

Look

closely at vintage hydroplanes. Other than the major discrepancies among

the different hydroplane builders, you can see very subtle variations.

If you attend a vintage raceboat event and see them sitting in the pits

side by side, these differences can be quite noticeable, even to somebody

who may not specifically be looking for them. There lies the beauty of

the different designs we see from one designer to the other.  But with so

few of these hydroplanes that have survived to this time today, photographs

can be the only evidence in quite a few instances where people are trying

to document or acquire a rare piece of racing history. But with so

few of these hydroplanes that have survived to this time today, photographs

can be the only evidence in quite a few instances where people are trying

to document or acquire a rare piece of racing history.

The

3-point hydroplane hull itself (if you can imagine the raceboat without

its sponsons attached) has been described as to an aircraft wing. The upward

slope of the bottom towards the nose provides the lift needed to plane

the hull above the water and on a cushion of air. Hence the name hydroplane.

These are basically low flying aircraft with a flying ceiling of a few

feet.

The top deck shape would be the

equilibrium providing enough air pressure resistance to keep the hull maintaining

its altitude especially at the higher speeds. The sponsons are the pontoons

mounted to each side of the hull which helps keep the hull balanced as

it crosses the water. The propeller, as on a airplane, provides the thrust

to keep it airborne.

The term 3-point hydroplane derives from the actual contact of the hull

to the water once it achieves enough speed to plane the hull on the cushion

of air. The 3 points that the hydroplane balances on as it skips across

the water being the first point of contact, the propeller, and the other

2 points being the ends of each sponsons. Interesting enough, decades went

by while boat racers kept trying to increase speed by increasing horsepower

to overcome the friction of the water.  There isn't anything built by man

that achieves what the hydroplane performs as it skips across the water

surface. There isn't anything built by man

that achieves what the hydroplane performs as it skips across the water

surface.

The

combination of all these principles becoming the unique experience we see

when you view one of these incredible craft. The sound of the open headered,

inboard engine, coupled with a high flying hull, and add about one ton

of water being displaced into the famous roostertail behind these machines

puts them atop anything I have ever experienced. The sheer eloquence as

they twist through a turn and the edge of the sponson kicks up another

roostertail has to be seen first hand to be appreaciated.

The hydroplanes throughout these

pages are the feat of engineering achieved its rich history. Quite an acheivement

considering the lack of computer modules that could have spewed forth some

of that information today.

The

foredeck of the different hull designs would include shapes on the crown

of the deck in order to find the optimum altitude of the hull throughout

its flight, whether it be the straightaways or turns. Proper placement

of weight being placed into the hull such as the motor, gas tank, battery,

and driver all combined to influence its attitude (proper weight distribution

for an even keel) and handling characteristics. Many competitive races

would be decided on these factors in matches where driver skills were comparable.

That is why a good driver was always looking for the right combination

in their hull to give them the best advantage possible. Just building the

right combination of proper placement of these items could be the difference

between a winner and loser. Considerations of the minimum weight restrictions

had to be followed. Considerations of extra weight was equally important.

This would be evident in time trials and on the kilo and 1-mile speed trap

runs. The straightaway records and heat records could be affected if you

were a heavy individual.

Times

and records broken could be inched up throughout a summer season. Every

little thing would be looked at. As with any racing endeavor, weight reductions

and maximum engine revolutions, even as minute as it may be seen, was closely

looked at. Superchargers were allowed in certain classes, but one had to

pay attention to the extra weight that was going to be incorporated into

the hull. Also, supercharged engines would need to carry additional fuel

that would be needed to feed the higher gas consumption used by a supercharged

engine.

The drivers would experiment with the gasoline blends trying to find the

specially brewed formulation using alcohol and nitro introduced to increase

horsepower. Any horsepower robbing items would be eliminated. Experimentation

was a rule of thumb. Engines would be tweaked between heats trying to fine-tune

their motors for every ounce of power available. Getting back to the hull

details, you will notice different transoms width and height that vary

from one design to another. The reasoning of these features are debatable

but time has already proven the winners and losers in these respects. The drivers would experiment with the gasoline blends trying to find the

specially brewed formulation using alcohol and nitro introduced to increase

horsepower. Any horsepower robbing items would be eliminated. Experimentation

was a rule of thumb. Engines would be tweaked between heats trying to fine-tune

their motors for every ounce of power available. Getting back to the hull

details, you will notice different transoms width and height that vary

from one design to another. The reasoning of these features are debatable

but time has already proven the winners and losers in these respects.

Innovation was the rule. Refinements were proven or disproven throughout

the summer racing season, some stuck, others were quickly thrown out. Others

yet would be refined, until they were proven right. These are some of the

reasons why it is great to go to a vintage event and see the stages of

evolution throughout the history of the different racing periods. Some

items might have worked in a smaller class, but would not work in a larger

class. Many factors influenced the subtle changes.

But as with most ideas, when a designer would try to improve on one aspect

of the hull, he could effect the good qualities and purpose and possibly

compromise other qualities and features.  Many a hulls were probably built

with good intentions only to be dismissed after a few races. I'm sure you

would get many an arguments with the designers on that subject. But whether

it was a proven winner or not, any racing hydroplane left around today

is a winner in my mind and worth being preserved. Hopefully, any left or

found today will survive the ax or firepit, and some good soul with invest

the time and money to bring it back to its original form for the pleasure

of all of us. Many a hulls were probably built

with good intentions only to be dismissed after a few races. I'm sure you

would get many an arguments with the designers on that subject. But whether

it was a proven winner or not, any racing hydroplane left around today

is a winner in my mind and worth being preserved. Hopefully, any left or

found today will survive the ax or firepit, and some good soul with invest

the time and money to bring it back to its original form for the pleasure

of all of us.

The

sponsons were the main idea that made the hydroplane a reality. You would

have to go all the way back to when Ventnor Boats Works had the original,

basic idea of attaching water skis on the front of a conventional displacement

V-hull to plane the hull up and out of the water. The success of this idea

quickly caught on and soon many raceboats were incorporating this thinking

into their hulls. Then the Ted Jones design of a 3-point hydroplane, first

used on Slo-mo-shun IV, rewrote the basic hull look we are seeing throughout

this article.  Ted Jones always believed that the top of the sponsons should

flow into the foredeck, were as some of other raceboat designers such as

Henry Lauterbach, Will Farmer and Rich Hallet, built their sponsons that

were offset from the foredeck. Ted Jones always believed that the top of the sponsons should

flow into the foredeck, were as some of other raceboat designers such as

Henry Lauterbach, Will Farmer and Rich Hallet, built their sponsons that

were offset from the foredeck.

Different

lengths, angles, heights, widths and placement of sponsons were tried throughout

history. First, there were the wet sponsons that was the rule, then the

exception. Dry sponsons (they would not fill with water) then became the

rule. Dry sponsons would aid the hull with buoyancy. But all these changes

contributed to the individual beauty of these racing hydros.

The cowlings were being built with

different shapes that would have lines to improve aerodynamics and help

with stability. A fin built into the rear cowling was from the thought

of helping stabilize the aft of the hull. Arguments can be made about the

effectiveness of this idea.

There

were also evolutions with regards to the "mechanicals" of a limited class

hydroplanes. The skid fin which aids the cornering of the craft in the

turns, was originally attached to the underneath of the hull inside the

starboard sponsons. Somebody moved the skid fin out further and angled

it slightly which was found to further aid the hull in the turns.

Another improvement was moving the 2 water pickups which were attached

to the ends of each of the sponsons to a single pickup that was attached

to the very bottom edge of the rudder. The water being picked up from this

location was much cleaner and eliminated the one-way valves that needed

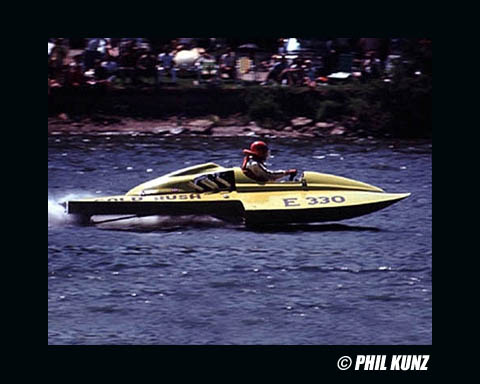

to be used for the sponson water pickups. As you can see in this photo,

there are many times when the sponson edges would be out of the water,

which would interrup the water flow to the engine.

A

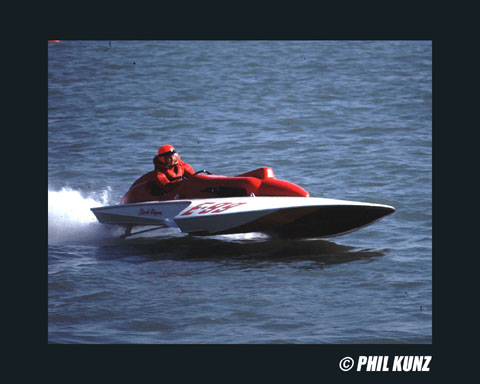

dividing point in the history of the inboards was the cab-over which started

being successful during the late 1960s. A few racers, (not builders) took

regular conventionals and moved the cockpit up in front of the motor. Two

of the conventionals that were converted were a Dick Sooy and Henry Lauterbach

design. There may have been more of them. A

dividing point in the history of the inboards was the cab-over which started

being successful during the late 1960s. A few racers, (not builders) took

regular conventionals and moved the cockpit up in front of the motor. Two

of the conventionals that were converted were a Dick Sooy and Henry Lauterbach

design. There may have been more of them.

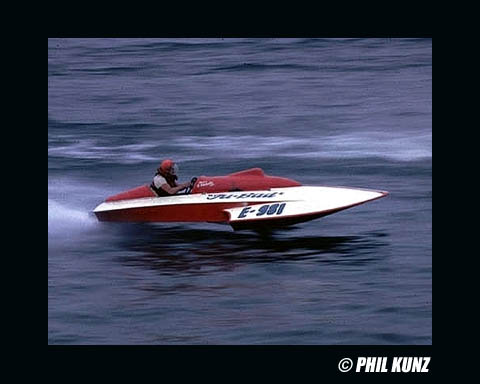

The

picklefork styled hydroplanes, with the driver in front (and currently,

usually enclosed in a capsule), and the motor behind him, started making

inroads in the late 1960's. In about 1963, Ron Jones started building round

nosed cab-overs which stayed that way until about 1966, when shallow pickelforks

were tried. The

picklefork styled hydroplanes, with the driver in front (and currently,

usually enclosed in a capsule), and the motor behind him, started making

inroads in the late 1960's. In about 1963, Ron Jones started building round

nosed cab-overs which stayed that way until about 1966, when shallow pickelforks

were tried.

This

was the beginning of the end of the traditionally styled, round nosed 3-point

hydroplane with the driver seated in the aft of the hull that everybody

was accustomed to seeing for about twenty-five years. During the early

1970's, the pickelforks on these racing hulls got deeper and became quite

popular. They started dominating in most classes by 1977. But the conventionals

weren't going away without a fight. Builders of the conventional hydroplanes

such as Lauterbach, Farmer, Hallet, Milosivich, Karelson and Staudacher

started making their transoms wider. This

was the beginning of the end of the traditionally styled, round nosed 3-point

hydroplane with the driver seated in the aft of the hull that everybody

was accustomed to seeing for about twenty-five years. During the early

1970's, the pickelforks on these racing hulls got deeper and became quite

popular. They started dominating in most classes by 1977. But the conventionals

weren't going away without a fight. Builders of the conventional hydroplanes

such as Lauterbach, Farmer, Hallet, Milosivich, Karelson and Staudacher

started making their transoms wider.

This

idea helped keep those designed conventionals in the win columns right

up to the late 1970's. Only in the extremely fast Grand Prix class did

the Lauterbachs hold their own up until 1989. This

idea helped keep those designed conventionals in the win columns right

up to the late 1970's. Only in the extremely fast Grand Prix class did

the Lauterbachs hold their own up until 1989.

These unique differences and evolution's

only add to the wonderful history of the sport of Hydroplane Racing.

The personality of handcrafted,

vintage hydroplane raceboats will remain as long as the spirit of vintage

hydroplane racing is kept alive through the next generation. The former

owners, drivers, designers, and builders of these racing crafts will be

remembered for their innovation and skill through the documentation, preservation

and restoration efforts of these unique flying hulls.

|